Mouth of the Saire River,

Bay of the Seine

I

NORMANDY INVASION

Artist unknown

How Aethelred, King of England, who married Emma, sister of the Duke, sent an army to conquer Normandy, and how Néel of Cotentin defeated and utterly destroyed this army.

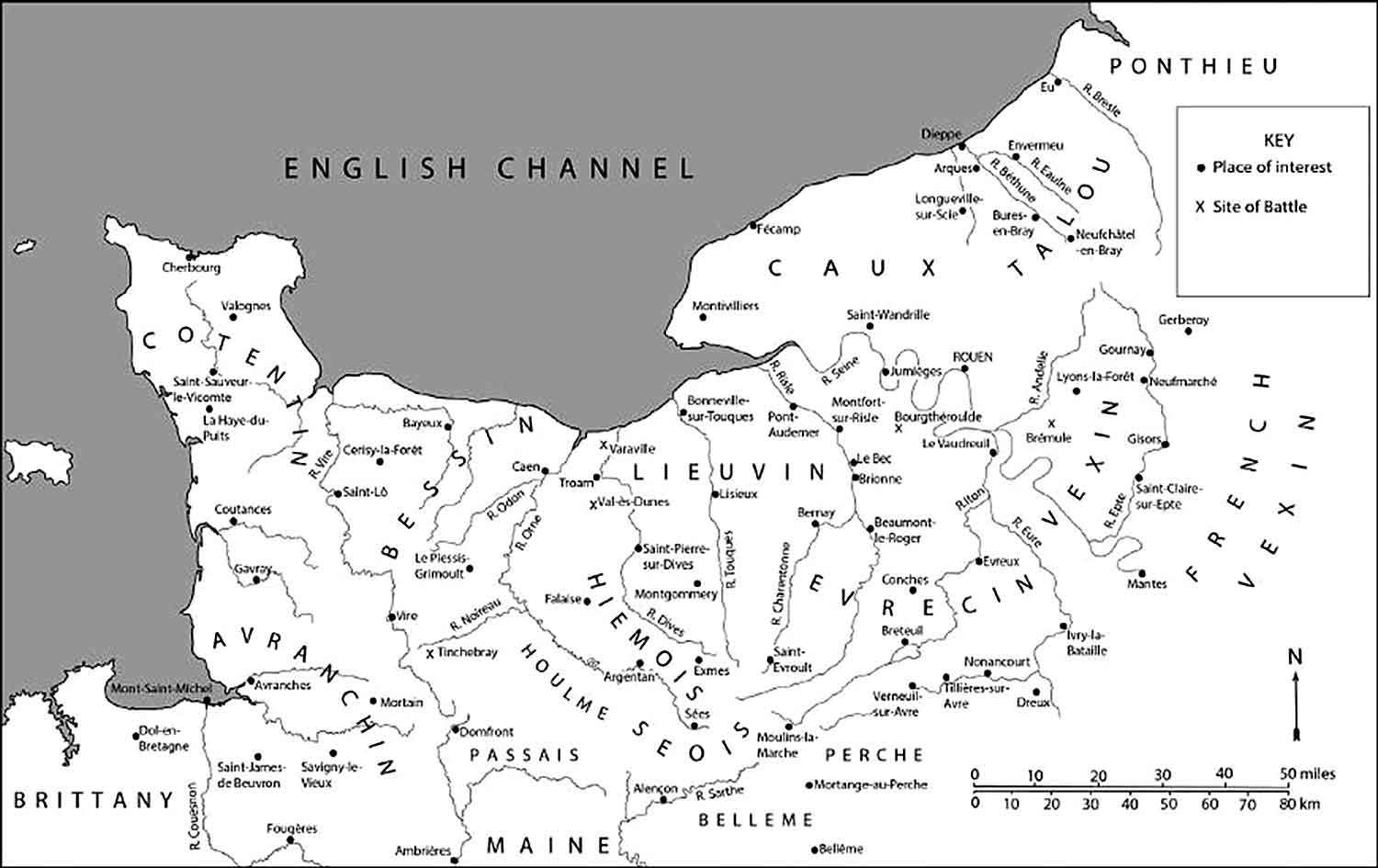

Except these invaders weren’t Vikings. By their leaders’ elaborate full-face helmets, their single-edged, clipped-point swords, and their banners – Roman-style windsocks in the form of golden wyverns, the two-legged winged dragons symbolic of Wessex – they would have shown themselves to be Anglo-Saxons, sent by their king Aethelred to punish the Norman duke Richard II for his flirtation with Vikings. The 11th-century monk William, of the Benedictine abbey at Jumièges in Normandy, was born right around the time of this raid, and devoted a chapter of his Gesta Normannorum Ducum (“Deeds of the Dukes of the Normans”) to it. According to him, Aethelred had ordered the raiders to lay waste Richard’s land with iron and fire: “He further commanded them to capture Duke Richard, bind his hands behind his back, and deliver him into the royal presence alive.” They had landed on the banks of the Saire River, which winds halfway across the Cotentin Peninsula to its outlet on the east coast. In their shallow-draft longships, the Vikings had routinely exploited river routes to penetrate deeply and unexpectedly into enemy territory. The Saire, however, today at least, is more of a winding creek, barely three or four yards across – deep enough to bear longships, but not wide enough to accommodate the sweep of their oars – and the Anglo-Saxons, as shall be seen, did not have the seagoing Vikings’ aversion to long overland marches. They beached on the tidal flats at the river mouth and waded across the rich offshore oyster beds which are still farmed to this day. Master Wace, the 12th-century Norman poet whose Roman de Rou, a history of the Norman people, probably used Jumièges as a source. He confirmed, “Disembarking, each tried to outrace the others, and quickly made their way to the beach. They took plunder and food, captured sheep and cattle and razed and burned houses. Women wept and peasants fled.” The English would find, however, that times had changed in Normandy. The kings of Francia relied on their Norman vassals to repel seaborne invaders, and the Normans took their royal duty seriously. It should be noted that historians regard accounts of this episode with various-sized grains of salt. Wace and Jumièges were Norman writers after all, writing to please their Norman patrons. No mention of the raid is made in English accounts, including any version of the Chronicle, which does mention Aethelred’s expeditions to Strathclyde and Man in 1000. Neither Wace nor Jumièges bother with exact dates, and those historians who take the story of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Normandy at face value date it anywhere from the 990s to 1003 or 1004. Most seem to settle around the turn of the millennium, but as the Chronicle notes, that year the English army and navy were in the north. In medieval times, men had to be home for the harvest. There was a narrow season for military campaigns, and it is doubtful Aethelred would have conducted two such wide-flung offensives in the same summer. More likely the English warred on their northern neighbors in 1000, and against the Normans in 1001. The Viking incursions in Devon and Somerset that year were much closer and more important to English scribes, to whom the Normandy landing may have been of little consequence. Since Aethelred, who led the northern invasions, evidently took no part in this one – presumably his hands were full with Forkbeard’s Vikings – it may even have been an unsanctioned raid by English pirates, simply played up for maximum political effect by the Normans. But England and France would be at war, on and off, for the next 800 years. If the Norman writers are to be believed, it was England that struck first. At the other, eastern end of Normandy’s flattened U-curve, across the Bay of the Seine from Cotentin, rises what the French call the Côte d’Albâtre, “the Alabaster Coast,” for its Dover-like chalk cliffs, a hundred meters high. Where the River Valmont cuts through them to the sea lies the village of Fécamp, today a modest fishing resort but a thousand years ago the seat of the dukes of Normandy.

Fécamp In the 990s, Richard I, the Fearless, Count of Rouen, raised an abbey on the hilltop overlooking the town, on the site of an old Merovingian nunnery destroyed by Vikings 150 years earlier, and the beginnings of a castle as well. (This was probably no more than a wood palisade, as the Normans were then only beginning to dabble in building stone castlework.) Around the turn of the millennium Duke Richard ordered the initial expansion of the keep, with a square wooden tower, in 1001 likely still under construction. Probably the growing family simply needed the extra room. Richard was only about twenty-one, but already married with two baby sons. His four brothers, three sisters and their Danish mother Gunnor were also crowded into his hall, but there was a prospect of some moving out soon.

Her birthdate is uncertain. In 1001 she could have been in her late teens, or not yet even a teen, but as shall be seen, she was probably near the higher end of the range. There are no images of her at this time, but she is said to have been “very esteemed and honored,” and “a very beautiful daughter, a well-behaved maiden.” Her brothers and sisters would go on to become variously counts, dukes, duchesses and an archbishop, but Emma would outshine them all. That, however, was all in the future. Right now, if the English had their way, it was possible the entire House of Normandy would be rendered abruptly and prematurely extinct.

Medieval Normandy If the English really wished to capture Duke Richard, as Jumièges asserts, it made little sense for them to land at the far end of the dukedom. To reach Fécamp from Cotentin would have required them to march practically around the whole curve of Normandy. There were probably a few of Forkbeard’s ships tied up at the town docks as well, possibly even something of a Danish fleet. A direct assault would mean fighting both Normans and their Viking allies. Medieval lords, however, often roamed at large over their realms and lived off their underlings’ largess, and the English may have hoped to intercept the young duke at the other end of his duchy, far from the safety of his fortress. If so, they were mistaken. The Val de Saire was the fiefdom of Néel I of Saint-Sauveur, the vicomte (viscount, vice-count) of Cotentin, Richard’s vassal on the peninsula. Normally his job entailed nothing more than enforcing ducal law and collecting taxes, but an Anglo-Saxon invasion brought out his Viking blood. Every Norman’s Viking blood. “He summoned liegemen and servants, knights and farmhands, townsmen, peasants and footsoldiers,” wrote Wace. “Even the old women came running with spears, cudgels and clubs, their skirts and sleeves rolled up, ready to fight.” This is probably his patriotic way of making the most of what was in fact a very typical medieval army – a small core of well-equipped, skilled fighting men that medieval Scandinavian scribes would call a hird, backed by a larger militia of poorly armed, ill-trained farmers and villagers that the English called a fyrd, all accompanied by various women and children, camp followers. Yet the lords of Normandy had a few surprises in store for the English. In the Val de Saire, Aethelred’s raiders were having their way with the locals. “From forest and field alike they seized and carried off loot, chased and hunted prey,” wrote Wace. “They beat and killed peasants and thought they could conquer the entire region.” The Anglo-Saxons warred in the manner of Vikings, surprising and overwhelming hapless country folk before any effective defense could be organized, preferring to avoid pitched battle. Yet by lingering too long in the Cotentin, they invited it. The Normans knew their home ground and could choose the point of attack. Somewhere along this venture, evidently on the march, the invaders were surprised by the oncoming rumble of hoofbeats. “Suddenly the men of the Cotentin were there,” wrote Wace, “and did not waste time making threats, but savagely attacked. Then you would have heard blows and shouting.” The scribes are vague on the details, but we know enough of Anglo-Saxon and Norman tactics to surmise how went the Battle of Val de Saire. For their part, the English fought like Vikings: on foot. Having to control a horse in battle was, to them, a needless distraction. “The Battle of Maldon,” an Old English poetic account of Anglo-Saxons fighting Olaf Tryggvason’s Norwegians just ten years earlier, tells how the English leader Byrhtnoth ordered his men to release their horses and chase them off prior to the fighting. The 12th-century English monk and chronicler Orderic Vitalis recalled, “The English scorn warhorses and, trusting in their ability, stand fast afoot.” The Normans, on the other hand, fought the way the Franks did, since the days of the Carolingian Empire centuries past: on horseback. The continentals had become well versed in cavalry tactics in Roman days, with a refresher course taught them by the Huns in the 5th century. Emperor Charlemagne’s armies had needed to cover ground in the course of his conquests, did so in the saddle, and eventually didn’t even dismount to fight. They developed a cavalry tradition, and passed it on to their Norman vassals. At Val de Saire, the Anglo-Saxons would have mounted their typical defense: a wall of shields, bristling with spears, two-handed axes adopted from their age-old Danish enemies, and their distinctive single-edged swords.*The Saxons’ iconic weapon, the seax or sax, from which they took their name, had evolved from a short dagger in the 5th century to a full-fledged short-sword by the 9th, yet always defined by its tapered, clipped point. The 10th-century Seax of Beagnoth, recovered from the Thames in 1857, has a blade almost two feet long, inscribed in silver and brass with the Anglo-Saxon futhorc and the owner or swordsmith's name, Beagnoth. It was probably a prestige weapon not meant for battle, but is similar in design to three other period blades found in southern England. The narrow point may have evolved from that of a utility knife into a stabbing weapon capable of penetrating and bursting links of chain mail. For their part the Normans would have attacked in their usual fashion: an all-out cavalry charge, with the aim of preventing the shield wall from ever forming or, failing that, of getting around and behind it. A shield wall could only face one way. Once broken or outflanked, it was defeated. Norman horsemen could ride down fleeing Anglo-Saxon footsoldiers, leaving the vengeful townspeople to finish off the wounded. “There was a great tumult and the battle was severe,” recorded Wace. “They killed and slaughtered everyone, as long as any Englishman still stood.”

Angus McBride, courtesy of Osprey Publishing The crews guarding the beached fleet were alerted to the disaster by the return of a single survivor. He had evidently sat down for a breather on the march and fallen behind before the Normans attacked. The sight of the massacre gave him a second wind, enough to run for his life. Wace has him telling the shocked sailors, “Flee, flee flee! If you hesitate you are all dead. If you are found here, you will be slaughtered like sheep…. Not one would live to be ransomed. Those you await are already dead.” Only enough English remained to man six ships, which they hastily slid off the tidal flats and sailed for home. When they arrived back at the English court, King Aethelred naturally inquired after the capture of Duke Richard. Jumièges has them admitting, “Most Serene King, we never saw the duke.” “You have lost all your men except us,” Wace continued. “You sent them to the slaughter and will not see them again…. There was a battle, a truly awful one, and misfortune fell upon us.” For Aethelred this was just the latest in a series of disasters. First Forkbeard demanding protection money and stepping up his predations regardless, and now this defeat of an English army at the hands of a petty duke and a people who weren’t even Viking anymore. His mother, the dowager queen Aelfthryth, passed away around this time. On top of that, his consort, Aelfgifu of York, had also just died. Some say she had been the daughter of an ealdorman, the king’s representative in Northumbria, others that she was of low birth, but in any case they had been together the better part of twenty years. She had given him six sons and three daughters, and may have died attempting to bear another. “He was filled with grief and sorrow for his commanders and his men. He regretted his foolishness and left Normandy in peace,” declared Wace. “What cheered Duke Richard caused the king great sadness.” In this first contest between Normans and Anglo-Saxons, the latter had come out second best. Unknown to the players, of course, the contest was to continue for over sixty years. For now, in his quest to make himself appear worthy of his Viking-conquering ancestors, the hapless king of the English would feel compelled to bully more helpless victims, even closer to home.

REVIEWS:

Mr. Hollway meticulously ties all of the elements together into a cohesive story and timeline…. Exhaustively researched and sourced, and exceptionally written, Mr. Hollway has assembled another masterclass in how to tell a multi-faceted story of history in one fell swoop. For those looking to get a grasp on early English history and the beginnings of the British monarchy, “Battle for the Island Kingdom” is a perfect selection. For those simply looking for a fun, yet bloody read, you can’t go wrong with Mr. Hollway’s latest.

This new book by Don Hollway ambitiously sets out to describe the complex interplay between competing European royal houses during what academics call ‘The Second Viking Age’.... Men and women feature in equal measure in the book, and family inter-relationships become important threads throughout the narrative. The author brings to life the Court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm.

The author brings to life the court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm. The narrative builds on the evidence of Scandinavian sagas, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the works of Norman historians.... Battle for the Island Kingdom is thoroughly enjoyable, and is recommended to anyone looking for a comprehensive and accessible history of the period.

In his latest work on this era, the author brings this period to vivid life through engaging prose, a coherent narrative and a mind for the most minute yet interesting detail. The references from relevant source material are plentiful but do not bog down the storytelling. This book is lively and easy to read. Most readers know about the Battle of Hastings and its outcome and while this book informs on that event, fewer know about the events leading up to it, but this work delivers that to the reader as well.

Hollway’s book is anything but dry. At every turn, he infuses his accounts with a novelist’s flair.... Hollway makes it feel so loud and headlong that the story feels both new and unpredictable. Just as with The Last Viking,� he’s filled a long-lost era with color and life.

Historian Hollway chronicles in this brisk study the 66 tumultuous years culminating in the Norman victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 CE…. Despite the outcome being well-known, Hollway’s suspenseful buildup during William’s rise as a credible threat to Harold pays off in his recounting of the epic battle. Throughout, Hollway explains frankly when source material may be questionable, and his footnotes clarify the path leading to the Norman Conquest. The result is an accessible and vibrant portrait of a turning point in world history.

There’s no need for fictional dragons when the real-life battle for thrones and empires is as thrilling as Hollway’s.... A deeply researched must-read for anyone interested in this contested era. Readers will be enthralled with quotations from period accounts and insights into the harsh reality of the violent, often short lives of Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman nobility. ORDER TODAY:

• AMAZON • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Author/historian/illustrator Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His first book, The Last Viking, a gripping history of King Harald Hardrada, was acclaimed by The Times of London and Michael Dirda, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Washington Post. Hollway is also a classical rapier fencer and historical re-enactor. His work is also available across the internet, a number of his pages scoring extremely high in global search rankings.

More from Don Hollway:

|

he sight would have been terrifyingly familiar to anyone living along the Channel coast in the centuries leading up to the turn of the millennium…that is, anyone lucky enough to have survived it the first time: longships, high-prowed, low in the water, closing in from the horizon with astonishing speed, oars sweeping across a high tide and hulls scraping to a halt on the silty shore. Men in chain-mail hauberks and leather byrnies, bearing shields and naked blades, leaping over the gunwales into knee-deep surf to wade onto foreign soil. And soon, the screams of victims and the glower of flames rising from thatched roofs.

he sight would have been terrifyingly familiar to anyone living along the Channel coast in the centuries leading up to the turn of the millennium…that is, anyone lucky enough to have survived it the first time: longships, high-prowed, low in the water, closing in from the horizon with astonishing speed, oars sweeping across a high tide and hulls scraping to a halt on the silty shore. Men in chain-mail hauberks and leather byrnies, bearing shields and naked blades, leaping over the gunwales into knee-deep surf to wade onto foreign soil. And soon, the screams of victims and the glower of flames rising from thatched roofs.