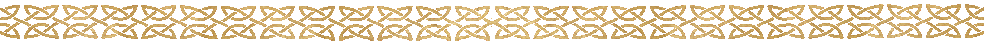

Mass burial,

Dorset Ridgeway, UK

II

FOREIGNERS

While Normandy prospered in the happiness I have recorded, Aethelred, king of the English, defiled the kingdom which had long flourished under the power of most glorious rulers, and committed a treason so appalling that even pagans judged this execrable crime horrible.

The death of the English queen, Aelfgifu of York, created an opportunity. Richard’s sister Emma would have been raised knowing it would be her duty to wed some foreign noble or another, as a bargaining chip in diplomacy and as a more-or-less hostage against any break in the peace. If she was to be married off, best to be married off to a king, and to a king of England at that. Norman women were more or less the property of their fathers or husbands, but Anglo-Saxon women could own land and slaves in their own name, sell it or give it away without a man’s consent, defend themselves in court, and even have their marriages annulled. Aethelred, then around thirty-five, was probably twenty-odd years older than Emma, but hardly an old man. To be the wife of a king, a mother of kings? Emma’s own mother and sisters must have looked on her with envy. Norman envoys found Aethelred amenable to such a match. According to Geoffrey Gaimar, an Anglo-Norman chronicler writing about twelve decades later, “These men advised that he should immediately cross the sea, ask for Emma, Richard’s sister, and bring her back. With the Normans as his friends, he could easily intimidate his enemies. Duke Richard would back him.” What middle-aged widower, particularly in those rough-hewn days, would refuse a beautiful girl in his bed, obliged to give him children? Eventually, of course, there would be a question of inheritance. Aethelred’s eldest son by the late Aelfgifu, the aetheling (prince) Aethelstan, was about Emma’s age, a warrior who would likely press his claim to the throne as rightful heir to the king. That was in the future. For now, there were myriad other details to be worked out. In Scandinavian terms there was the brydceap, the “bride-price” the groom gave her family to compensate them for the loss of such an asset; the brydgifu, the “bride-gift” or dowry that her family provided her as security in the event she was widowed or divorced; even the morgen-gifu, the “morning gift” or dower to be presented by the groom to his new wife as the price of her virtue. These were not small matters. Among his wedding gifts, Aethelred gave Emma properties in Winchester, Northamptonshire, Devonshire, Suffolk and Oxfordshire, not to mention the entire city of Exeter.

Anglo-Saxon king with his councilors, the witan. Such negotiations took time, especially since Aethelred’s rule was not absolute or even hereditary in the manner of feudal, continental rulers. Anglo-Saxon kings did little without the approval of the witan, the “wise men” of the advisory council. (The Vikings would have called the meeting a thing.) It was they who confirmed new monarchs, theirs the choice of making a Norman girl an English queen. Evidently they were not opposed, but it was not until Lenten season of 1002 that Emma and her bridal party, including her personal retainers and men-at-arms, made the Channel crossing. The first meeting of the new royal couple must have been quite the experience for all concerned – a match not only of politics, but matrimony, akin to a president of the United States not just meeting, but marrying, the Queen of England, or more accurately of some non-English-speaking country. Unless they were mutually educated in Latin, Aethelred and Emma might even have needed an interpreter, since Old English and Old Norman were not the same and not yet widely spoken outside their native lands. According to Wace, “The Normans claim the English bark, because they cannot understand their speech.” Decades later the monks John and Florence, in the cathedral at Worcester on the River Severn, had never met Aethelred, but knew church elders who probably had. They described him as “a youth of good manners, handsome appearance, and fine personality.” That, however, was Aethelred as a young man. He was no longer young, and beaten down by years of near-constant defeat and submission at the hands of the Vikings. Whatever Emma thought of him was not written down, for in those patriarchal times it was immaterial. Of her Gaimar would write, “A more beautiful woman there could not be,” but he wrote that over a century later, without ever knowing anyone who had ever met her. Whether Aethelred was happy with his new bride (and to judge by his future behavior, he was at best ambivalent) was equally immaterial. This slip of a girl – half-Danish, half-Norman, all Viking – was the future of England. Her new country, and subjects, must have presented something of a culture shock to a Norman noblewoman. “The English in those days,” wrote the 12th-century English chronicler William of Malmesbury, “wore short tunics reaching to the mid-knee. They had their hair cut short and their beards shaved. Their arms were laden with golden bracelets and their skin decorated with tattoos.” From the crumbling Roman ruins on the coast, Watling Street – Wæcelinga Stræt, the “street of the people of Waecla,” today’s A2 or Great Dover Road – led through hamlets of what Malmesbury disparaged as “mean and despicable houses,” little thatch-roofed, wattle-and-daub shacks very unlike the “noble and splendid mansions” of the Normans and French, peopled with dirty peasants muttering in their strange guttural tongue as she passed. But then, whether a French paisant or English ceorl (churl, lowest of the low, little better than a slave), a commoner was a commoner on both sides of the Channel. As queen, Emma would not have to associate with her husband’s subjects any more than she had her brother’s.

Cantwaraburh The 400-year-old cathedral at Cantwaraburh, modern Canterbury, “the city of the men of Kent,” had already been rebuilt at least once, along the lines of a Roman basilica (in fact, on the site of an old Roman-era church). It was even then one of the largest in Europe, as befit the cathedra (Latin, “seat”) of the church in England. No descriptions of royal wedding ceremonies survive from this period, but in its cavernous interior, echoing with the hymns of the choir, repeating her vows in Old English from rehearsed memory, Emma was married to King Aethelred, anointed and crowned as his queen consort. Her name in Old English being Imme or Imma, she was given the regnal name Aelfgifu, the same as her husband’s dead wife, but more likely in remembrance of his sainted late grandmother. Meaning “elf-gift,” it was a common Anglo-Saxon girl’s name; Aethelred also had a daughter named Aelfgifu. In his chronicle of the royal family, the 13th-century monk and artist Matthew of Paris enthused, “They were beautiful as sapphire and glittering gold, or the lily and the rose in bloom.” But the Chronicle, a copy of which was maintained at Canterbury, reveals the somewhat cooler attitude of Emma’s new subjects toward her: merely that “the Lady [Hlæfdige, meaning queen], Richard’s daughter, came to this country.” And there is no record of what Aethelstan Aetheling and his brothers, Ecgberht and Edmund (who were about Emma’s age), thought of the match. They surely attended the wedding ceremony, but for them Queen Emma was nothing but a threat. Thus was peace made between England and Normandy. Yet there were still the Danes to contend with. That year Aethelred had already paid them 24,000 pounds silver. These payments had been going on now for ten years, with no sign of abating. After so many years of conquest, many of the invaders had simply settled on English soil as unassimilated immigrants, as Wace recorded: “In England the Danes lived alongside the English, married English women and raised many sons and daughters. They had had lived there so long that they had greatly increased their number and power. The English thoroughly hated them, but could not rid themselves of them, for they did not dare meet them in battle.” Their foreign ways were anathema to right-thinking Anglo-Saxons, or at least the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy. Malmesbury was half-Norman on his father’s side, and had a low view of his Saxon mother’s people:

Anglo-Saxon feast, 11th century. The clergy, content with the slightest degree of learning, could barely mumble their way through sacraments, and anyone with a knowledge of grammar was beheld with awe and amazement. The monks ignored their order’s rules, wearing fine vestments and enjoying every kind of food. The nobility, giving in to luxury and debauchery, did not go to church in the morning like good Christians, but simply, carelessly heard prayers and services from a hurried priest in their chambers, along with their wives’ flattery. The defenseless commoners became prey to the powerful, who made fortunes by either seizing their goods, or by selling them bodily in foreign lands, although it is characteristic of this people, to prefer revelling, rather than accumulating wealth. “Drinking at parties was common practice, at which they passed entire nights as well as days,” he added. “They were accustomed to eat until they became glutted, and to drink until they were sick.” On the other hand, John of Wallingford, a 13th-century Benedictine monk at the Abbey of St. Albans, famously declared the Danes did not have to kidnap Anglo-Saxon ladies to steal them away. They simply practiced good manners, kept their hair combed, bathed weekly, changed clothes regularly, and smooth-talked English wives and daughters into their beds, the cads. Ethnic hate was rife among the Anglo-Saxon populace, especially as whipped up by Wulfstan, the firebrand Bishop of London. England could absolve itself of the sins for which God had punished it with Vikings, he promised, by driving them out in turn. And Wulfstan sat among the witan, where he would have recommended such a course to the king. Aethelred was informed there was a plot afoot among the Danes settled in the country. According to the Chronicle, “The king was advised that they wished to kill him, and all his councilmen with him, and then seize the kingdom.” Once a Viking, always a Viking. If the English could not eliminate the Danish threat on the battlefield, or by bribery, then they would accomplish it by guile. Never in his long reign was Aethelred, the Ill-Advised, so ill advised. In January 2008 laborers on a construction site at St. John’s College in Oxford had to halt work upon striking archaeological gold. Among the finds uncovered by specialists called to the site were a Stone Age earthwork enclosure, pottery, the remains of food, and a mass grave: human skeletons dumped together so haphazardly that a month was required to excavate them all, and two years to count them – between thirty-four and thirty-eight; even the experts could not piece enough together to be sure. Bone analysis indicated they were Scandinavians, all males. All had suffered appalling cut and puncture wounds. Many had skull fractures. Some of the bones were charred. Radiocarbon analysis narrowed the date of burial to between AD 960 and 1020. In June 2009 another mass grave was uncovered, this time at Ridgeway Hill, down in Dorset: over fifty dismembered skeletons, dumped in an abandoned Roman-era quarry. Again, all males, in their teens to mid-twenties, their wounds not indicative of death by battle, but by execution – decapitation. Their skulls were all piled together off to one side, but only fifty-one of them, three heads having been retained, presumably as trophies or souvenirs. As before, the date of death was estimated at AD 970 to 1025. Though nothing is certain, historians have linked these atrocities to a specific day in English history: November 13, 1002, the feast day of St. Brice of Tours, a 5th-century Frankish bishop reviled for his youthful decadence but later venerated for his humility. The date was not random but carefully chosen. St. Brice’s Day is two days after the feast day of St. Martin. Traditionally Martinmas marked the start of the slaughtering season, when all the country folk brought their fattened cattle, sheep, poultry and other livestock into town for butchering and marketing – along with all their axes, cleavers and knives. After consultation with his witan, Aethelred chose St. Brice’s Day to put his plan into action. Jumièges scoffed, “The king, driven by a blind hatred and without accusing them of any offense, ordered the peaceful Danes of his kingdom to be massacred.” Aethelred himself admitted as much a couple years later, in a royal document: “I sent out a decree as advised by my lords and magnates, ordering that all the Danes living in this island, sprouting like weeds amongst the crops, were to be slain by a most deserved extermination, and so this decree was to be put into effect even unto death.” “The plans and the treachery were so well hidden,” wrote Wace, “that they were all slain at one and the same time, wherever they were found.” In England the event is remembered as the St. Brice’s Day Massacre. Across the North Sea it is called the Danemordet, the “Danish murder.” Today the practice, like more recent activities in Armenia, Germany, the Balkans, Rwanda and more, would be called by other terms. Genocide. Ethnic cleansing. Extermination. “With great knives and axes they slit their throats,” attested Wace. In Dorset, it is thought the prisoners were stripped naked and beheaded from the front, so they could stare their deaths in the face. In Oxford it was mob violence. The Danes sought refuge in St. Frideswide’s, the minster church named after the town foundress. The townspeople locked them inside and set it afire, incinerating them. The 13th-century English chronicler Roger of Wendover reported, “The decree was mercilessly carried out in London town, to the point that a number of Danes who sought refuge in a church were all butchered in front of the very altars.” Nobody knows to what extent the sentence was carried out. Wace wrote, “They slew and murdered so many that no one could count the dead and left many unburied.” In the old Danelaw, the greater part of the population would have had Danish blood. Maybe the victims were only Scandinavian mercenaries in English service – the mass graves in Oxford and Dorset hold only men – but according to the chroniclers, women and children were not spared. Wace went into horrific, possibly overwrought detail: They dragged babies out of their cradles and smashed their heads against the doorposts, knocking their brains out. Some they disemboweled. The women and maidens they buried in the earth up to their breasts. Then they loosed their mastiffs, their dogs and hounds, who tore out their brains and ripped off their breasts. They left no Dane alive, man, woman or child. Legend has it that one woman was specifically targeted: Gunhilde Haraldsdottir, wife of Pallig Tokesen. A Dane who had entered English service, Pallig had been named by Aethelred as Ealdorman of Devonshire and become rich, but soon reverted to his Viking ways and joined the plundering of AD 1001. Gunhilde was a Christian and had pledged herself to peace, but now the whole family, taken prisoner, was to pay the price for her husband’s treachery.

The Massacre of St. Brice’s Day According to Malmesbury, one Eadric Aethelricsson (more of him later) acted as the king’s enforcer: “In his cursed fury, Eadric ordered her, even though knowing that her death would bring great evil on the entire kingdom, to be beheaded with other Danes.” Gunhilde’s husband Pallig was executed in front of her, and likewise their son, speared through four times, before Gunhilde faced the sword. Wendover recalled her bravery: “She confidently predicted in her last moments that her death would cause great damage to England.” “She suffered her end with courage,” attested Jumièges, “and she neither paled at the prospect, nor, when dead and her blood stopped, did she lose her beauty.” Gunhilde Haraldsdottir was singled out for mention in the chronicles not just because she was the wife of a Danish ealdorman. She was the daughter of Harald Bluetooth, once King of Denmark. And the sister of Svein Forkbeard.

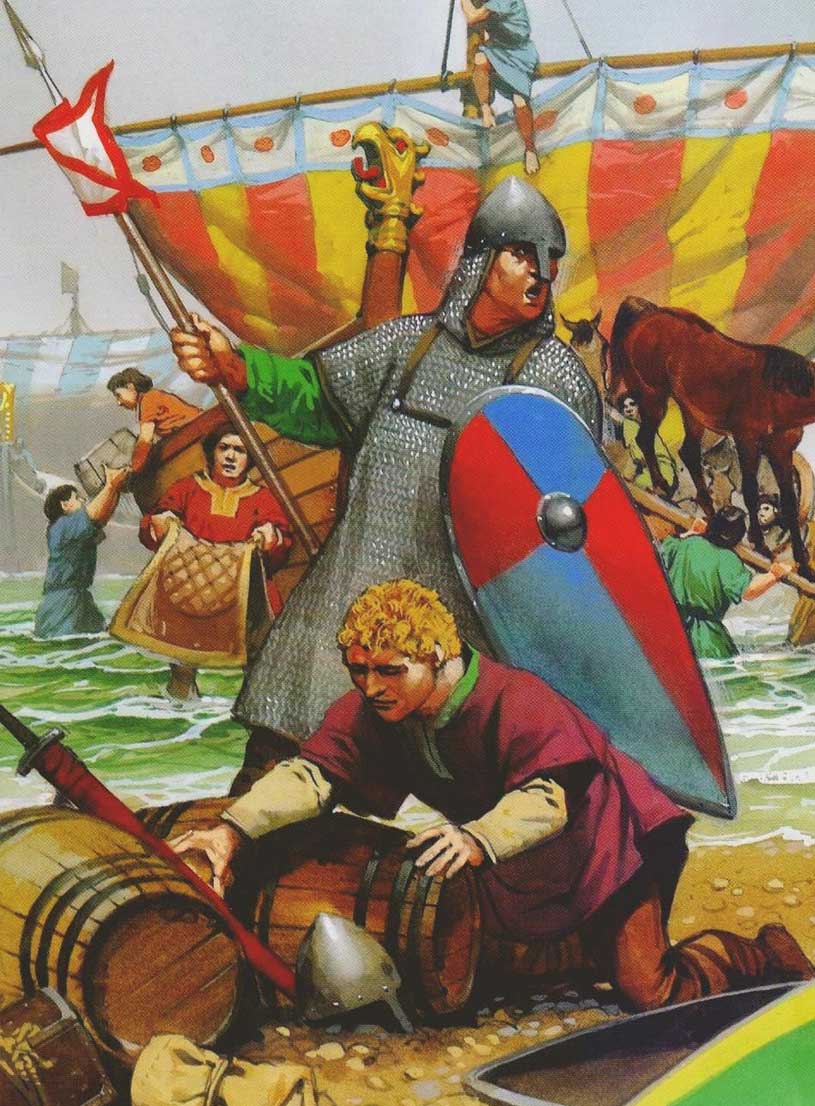

The Battle of Hastings by Tom Lovell.

THE BATTLE FOR THE ISLAND KINGDOM REVIEWS:

Mr. Hollway meticulously ties all of the elements together into a cohesive story and timeline…. Exhaustively researched and sourced, and exceptionally written, Mr. Hollway has assembled another masterclass in how to tell a multi-faceted story of history in one fell swoop. For those looking to get a grasp on early English history and the beginnings of the British monarchy, “Battle for the Island Kingdom” is a perfect selection. For those simply looking for a fun, yet bloody read, you can’t go wrong with Mr. Hollway’s latest.

This new book by Don Hollway ambitiously sets out to describe the complex interplay between competing European royal houses during what academics call ‘The Second Viking Age’.... Men and women feature in equal measure in the book, and family inter-relationships become important threads throughout the narrative. The author brings to life the Court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm.

The author brings to life the court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm. The narrative builds on the evidence of Scandinavian sagas, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the works of Norman historians.... Battle for the Island Kingdom is thoroughly enjoyable, and is recommended to anyone looking for a comprehensive and accessible history of the period.

In his latest work on this era, the author brings this period to vivid life through engaging prose, a coherent narrative and a mind for the most minute yet interesting detail. The references from relevant source material are plentiful but do not bog down the storytelling. This book is lively and easy to read. Most readers know about the Battle of Hastings and its outcome and while this book informs on that event, fewer know about the events leading up to it, but this work delivers that to the reader as well.

Hollway’s book is anything but dry. At every turn, he infuses his accounts with a novelist’s flair.... Hollway makes it feel so loud and headlong that the story feels both new and unpredictable. Just as with The Last Viking,� he’s filled a long-lost era with color and life.

Historian Hollway chronicles in this brisk study the 66 tumultuous years culminating in the Norman victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 CE…. Despite the outcome being well-known, Hollway’s suspenseful buildup during William’s rise as a credible threat to Harold pays off in his recounting of the epic battle. Throughout, Hollway explains frankly when source material may be questionable, and his footnotes clarify the path leading to the Norman Conquest. The result is an accessible and vibrant portrait of a turning point in world history.

There’s no need for fictional dragons when the real-life battle for thrones and empires is as thrilling as Hollway’s.... A deeply researched must-read for anyone interested in this contested era. Readers will be enthralled with quotations from period accounts and insights into the harsh reality of the violent, often short lives of Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman nobility. ORDER TODAY:

• AMAZON • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Author/historian/illustrator Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His first book, The Last Viking, a gripping history of King Harald Hardrada, was acclaimed by The Times of London and Michael Dirda, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Washington Post. Hollway is also a classical rapier fencer and historical re-enactor. His work is also available across the internet, a number of his pages scoring extremely high in global search rankings.

More from Don Hollway:

|

n Normandy, Duke Richard was in a predicament. His duchy had been gifted to his great-grandfather Rollo by the King of France as a buffer state against Viking invasions. The dukes had solved that problem by making the Scandinavians partners in trade, but perhaps the only thing they had traded was one set of invaders for another. The defeat of Aethelred’s raiders was no guarantee the Anglo-Saxons would not come again, and in greater strength. Normandy was on only intermittently good terms with its neighbors in France and Brittany, and Richard’s own vassals might rise against him if he showed weakness. He had made peace with Forkbeard. Now he needed to make it with Aethelred.

n Normandy, Duke Richard was in a predicament. His duchy had been gifted to his great-grandfather Rollo by the King of France as a buffer state against Viking invasions. The dukes had solved that problem by making the Scandinavians partners in trade, but perhaps the only thing they had traded was one set of invaders for another. The defeat of Aethelred’s raiders was no guarantee the Anglo-Saxons would not come again, and in greater strength. Normandy was on only intermittently good terms with its neighbors in France and Brittany, and Richard’s own vassals might rise against him if he showed weakness. He had made peace with Forkbeard. Now he needed to make it with Aethelred.