Old Minster foundation,

Winchester Cathedral

PROLOGUE:

A NEW MILLENNIUM

Winchester Cathedral

We, too, should translate those books which are of highest importance for most men to understand…until they learn how to read English writing. Let men afterwards also teach Latin to willing students, whom they desire to educate to a higher state.

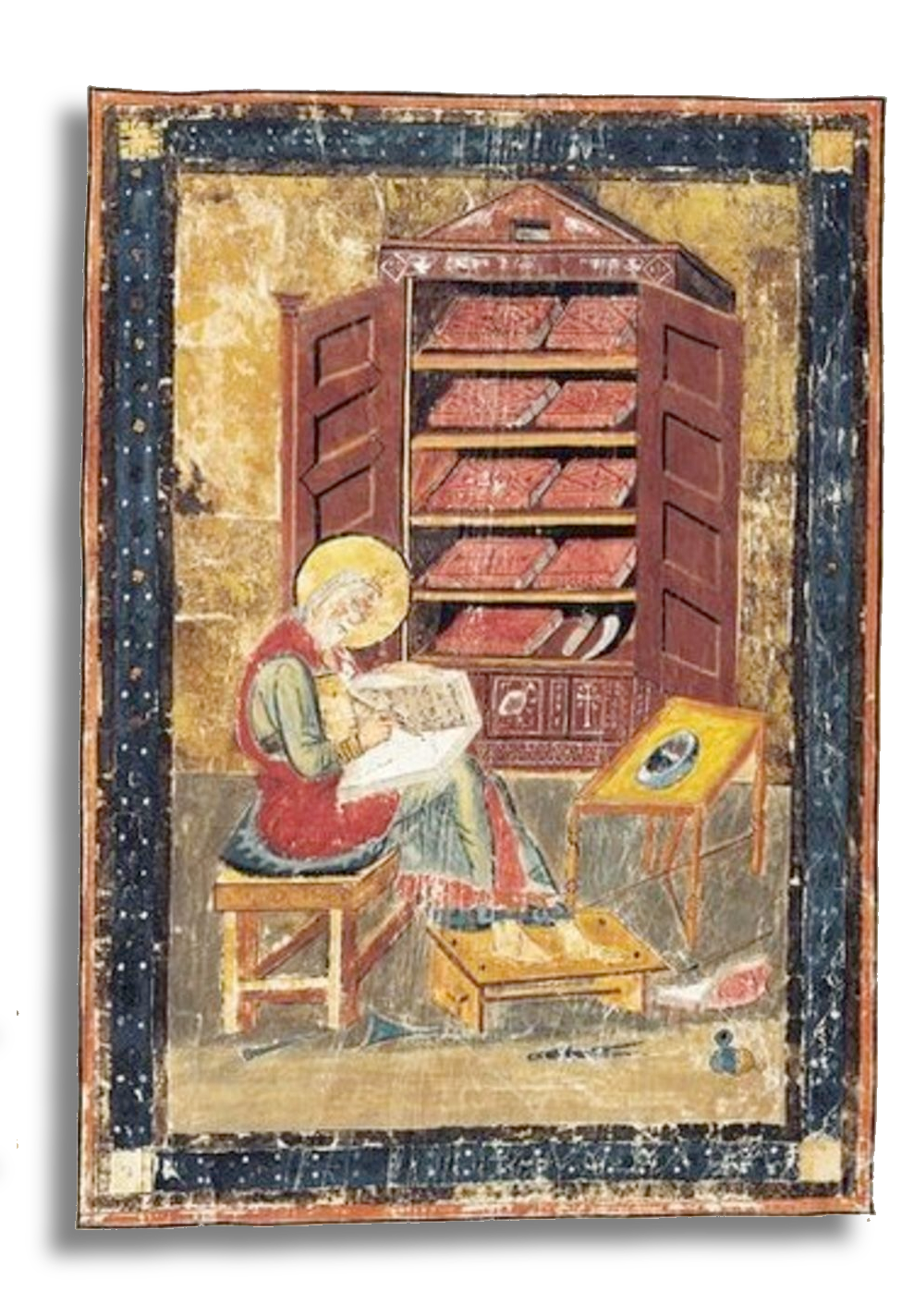

Winchester’s Anglo-Saxon Old Minster (Reconstruction) Those outlines were there when Winchester was Wintanceaster, the capital of Wessex (to the extent there was one) and, for much of the island's subsequent history, of Anglo-Saxon England. They trace the foundations of the town's Old Minster, the church that stood on the site for over 400 years prior to the construction of the modern cathedral, and probably for a good 200 years before St. Swithun himself was born. More modest than its replacement, the Old Minster nevertheless had been one of the largest, most impressive and most important buildings in England. In those days churches were not only the center of civic life but seats of learning, home to the very few people who were literate: monks, priests and clergy. Sons of nobility, and some daughters too, were sent to monastic schools to learn Latin and, as shall be seen, written English (then, Old English). Churches became repositories of knowledge, where books of the day were laboriously copied by hand in monastic scriptoria and stored in their libraries, bibliothecae.

Medieval scribe. A thousand years ago, in the scriptorium of Wintanceaster's Old Minster, an anonymous scribe sat bent over a writing table, carefully replicating, word by word, a medieval folio, itself perhaps a hundred years old. Every step of the process required meticulous labor. Lamb-, kid- or calfskin vellums had to be soaked in urine to remove flesh and hair, then washed, scraped, stretched and dried before being cut into sheets and scored with parallel scratches to mark lines and margins. Black ink was manufactured from crushed oak galls, scarlet from red mercury and egg white, and green from malachite, all using gum arabic from African acacia trees as a stiffener and applied with quill pens. Wing feathers from geese or swans (the curvature of left-wing feathers being preferred by right-handed scribes) constantly needed their quills sharpened, up to sixty times a day. Each scribe kept a small knife ready in his off hand for that purpose, and to scrape away errors in transcription before the ink set on the skin. The work was slow, tedious, and exacting. As a result of all this intensive labor, books were incredibly valuable. Our medieval scribe at millennium's end would not be working on mundane texts. Among many others, of course, he – or they, as, to judge by the handwriting, over the centuries up to fifteen monks carried on the work at Winchester alone – was updating a year-by-year recounting of people and events, the greatest annal in early English history. It had no known title in its day. The first printed edition, in 1692, was arbitrarily titled the Chronicon Saxonicum. Since 1861 it's been known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Its writing had probably first been undertaken right there in Winchester, by the vision and at the command of King Alfred the Great (r. 871-899). Knowing that his capital was constantly at risk from a sack by Vikings, most of whom considered books as little more than handy fire starters, he had seen to it that copies of the original were sent for safekeeping to monasteries across England – Abingdon Abbey, Worcester Cathedral, Peterborough Abbey and others, probably including a number whose copies have been lost. (Today at least seven editions and a number of fragments survive, though not all date to the beginning of the millennium, being transcribed later. The copy from Winchester is thought to be third-hand, a copy of a copy of the original.) Each site updated its edition independently, sometimes taking secondhand news, rumor and hearsay as fact. This naturally led to some divergence, discrepancies and errors, and only by comparing and contrasting the various accounts can something of a consensus be made. Taken as a whole, however, the Chronicle offers the first post-Roman European history written by a people in their own language. Its earliest entries far predate its actual inception, going as far back as 60 BC, the date of the Roman invasion of England, and a genealogy in the Winchester chronicle claims the descent, and therefore the legitimacy, of West Saxon kings all the way down from Adam. For events prior to Alfred’s reign the annalists could draw – as might we – on earlier historians and their monastic forebears. Even after the fall of Rome, many of these historians continued to write in Latin, in which even Anglo-Saxon clergymen were educated, and as would their counterparts on the Continent, the anonymous authors of, say, the Encomium Emmae Reginae and Vita Aedwardi Regis. Alfred, however, recognizing that few of his subjects spoke the Roman tongue, and that most were illiterate and would never read the annals themselves, decreed that an Anglo-Saxon chronicle should be written in Anglo-Saxon English, for an Anglo-Saxon audience. With its reliance on alliteration (both vowels and consonants), Old English was meant to be heard, not read. But Anglo-Saxons might listen to their history read to them by a cleric educated in Latin, who in turn might not be able to read the old Scandinavian runic alphabet, the futhorc. So the scribes used Roman lettering to approximate Old English word sounds. The difference is telling, and important. In medieval society the Church’s mastery of the written word gave it control of narrative, of recorded history – in effect, of the truth. The writers of the Encomium and the Vita wrote on behalf of aristocratic sponsors, to present their version of events for posterity, and the annalists of the Chronicle likewise, on behalf of the king in the name of the English people. By recording Old English words in the Latin script popular across the rest of Europe, Alfred was striving to preserve his people’s heritage for foreign readers as well, to prove them worthy of inclusion among the great peoples of history. For hundreds of years that worthiness had been in dispute. Most of England, except for Wessex and Mercia, had long been under Danish domination, in effect part of Scandinavia. The Anglo-Saxons considered Viking depredations as God’s divine punishment, perhaps for the crime of allowing their own culture to decline so far from the greatness gifted them by Rome. The annalists, ticking off the years on their pages, could attest that, more than a century after Alfred’s death, Anglo-Saxon versus Viking was still an ongoing struggle. It had always been the Island Kingdom’s curse to be just visible enough to observers across the water, to tempt the boldest to try conquering it. Before the Romans it had been the Celts, crossing the Channel from Gaul. It was a Celtic tribe, the Belgae, who had settled the site of three Iron Age forts and called it Wenta or Venta, “town.” The Romans, when they in turn conquered the Belgae and fortified the place, named it Venta Castrum, “town castle.” The Romans themselves had been, if not the most enduring, by far the most advanced and successful of these waves of invaders. Over more than 350 years they had cultivated a high level of art, culture and engineering among the natives, enforcing a kind of Pax Britannia. By the end of their tenure, though, when their own empire was falling apart at home, the island’s eastern coast was already plagued with Germanic raiders: Jutes, Angles, Saxons. In the power vacuum left by Rome’s departure, these had come to stay, either assimilating the native Celts or driving them into Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. (It was the Germanics who had named the ex-Roman town Wintanceaster.) For four and a half centuries these Angles and Saxons mingled, interbred, founded kingdoms, and ultimately fell to fighting among themselves. First the king of Kent took dominance, then the lords of Northumbria and Mercia, then Wessex. They had proven unable to unite to form a common front when a savage new breed of raiders, Scandinavians whom they called the Denes, the Danes, arrived to prey on them as they had once preyed on the Celts. Their mindset in those hard-pressed years is probably best captured in the Codex Exoniensis, the “Exeter Book,” a collection of Anglo-Saxon poetry dating from the late 10th century, though probably composed much earlier. The poems are full of lament and woe, mourning lost loved ones and dead lords. Looking back, the 12th Century Cistercian abbot Aelred of Rievaulx described those times simply: “Fear, death, desolation, and mourning reign everywhere.” Only Wessex and Mercia held out against the Danish onslaught, and those only by the virtue of Alfred’s guile and force of will. He saw all Anglo-Saxons as one people, the Angelcynn, the English race. Together they withstood the Viking pressure, and began to push back. In 878, at the Battle of Edington, Alfred defeated the Viking king Guthrum, had him baptized under the Englisc name Aethelstan, and named him king of East Anglia. The peace was uneasy. In 885 Guthrum resorted to calling the Viking chieftain Hrolf away from his siege of Paris to help put down an uprising among his subjects. According to the Picardish historian of the Normans, Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Hrolf dropped his siege and came to England, pledging Guthrum he would remind the Anglo-Saxons of the Vikings of old: I will crush whomever you please, I will destroy whomever you choose. I will level their cities and I will set fire to their houses and villages, I will tread them underfoot and scatter them, I will make them your slaves and kill them, I will take their wives and children captive and I will devour their herds.

Anglo-Saxons vs. Vikings Hrolf made good on his promise. After Guthrum was restored to power, he was so grateful (according to Dudo) that he offered the Viking half his kingdom to stay in England. Hrolf nobly declined, choosing instead to return to Francia. Though he never did conquer Paris (if he had, it might have changed European history as much as a later invasion of England by his descendants), the Franks ceded Neustria, the western, coastal part of their kingdom, to him. Over successive generations, as shall be seen, that land and its people – part French, part Viking – would acquire a new name, the same way Hrolf would be remembered as their father, Rollo. Meanwhile in England, for 70 years Anglo-Saxons and Vikings maintained an uneasy, troubled equilibrium, but when the last Norse ruler of York, Eric Bloodaxe, died in 954, in battle or murdered, the Danish tide finally washed back out to sea. What had been Britannia under the Romans, Britene, Brytene or Britenlond among the Germanics, and the Danelaw, Mercia, and Wessex to Alfred’s Anglecynn, was now united as one: the Angelcynnes lond, Aenglelande, Engla-land. The northern Anglo-Saxons, though, having lived so long under Viking rule, were half-Viking themselves, clinging to Scandinavian ways. In the 980s the Danes returned, and though they did not manage to reestablish their ancestral Danelaw on English soil, they soaked it in blood. For the entire reign of English King Aethelred II (at 37 years, the longest of any Anglo-Saxon king), Vikings were the bane of his existence. Not for nothing would he become infamous as Aethelred Unraed, “the Unready.” He had tried fighting, but at Maldon in 991 the Norwegian reiver Olaf Tryggvason dealt his army a decisive defeat. Aethelred then tried to buy them off, but payments of gafol, later to be known as Danegeld, the “Danish tax” or “Danish tribute,” only encouraged more raiding. In 994 Tryggvason allied with the Danes under King Svein Haraldsson, called Tjuguskegg, Forkbeard. They returned to besiege Lundenburh, Fort London, built within the walled confines of Roman Londinium, already the largest city in England and Aethelred’s capital. Both Tryggvason and Forkbeard were Christians, but apparently only Olaf had a Christian conscience. Aethelred and Winchester’s bishop Aelfheah prevailed upon him (with the added encouragement of 16,000 pounds of gold and silver) to agree to raid England no more. Olaf had gone home, become king, and forcibly converted Norway to his faith. In England, for the time being, it had seemed the Viking menace was over. But now Olaf was dead, outnumbered, surrounded and slain at the naval Battle of Svolder in the western Baltic, by his erstwhile ally Forkbeard. Nor was Forkbeard, so cruel that he had driven his own father Harald Bluetooth to death in exile, satisfied to be king of Denmark and Norway. He had turned avaricious eyes toward England, which in those days was seen as the most southerly, warmest part of Scandinavia. Vikings raided right up the Thames, laid waste almost all of Kent, and threatened London, while the Chronicle lamented Aethelred’s feckless response: The king and his councilmen decided to move against them with both the army and navy, but every time the ships were ready there was a delay, which was very annoying for the eager sailors aboard. Again and again the more urgent anything was, the longer it took to begin it. Meanwhile they were allowing their enemies’ strength to increase, and whenever they retreated from the sea the enemy moved closer. When all was said and done these naval and army plans were an utter failure, succeeding only in alarming the people, wasting money, and encouraging the enemy. Aethelred did, however, manage to take out his frustration on any neighbors who supported the Vikings. He marched his army north to ravage Strath-Clota, “valley of the river of (the Celtic goddess) Clota,” in Alba, modern Strathclyde in Scotland. His fleet raided the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea. And the English chroniclers, in charting the Vikings’ depredations, took note to add one more hostile neighbor to their list: “The enemy fleet had sailed off to Richard’s realm.” This realm, just across the English Channel (which the Anglo-Saxons called the Sud-see, South Sea) was the dukedom of Richard II of Normaundie, modern Normandy. Unlike the Danes in the Danelaw, however, and more like the Angles and Saxons in England, rather than remain a Scandinavian colony the descendants of Rollo had interbred and assimilated with the local Franks and Celts, becoming vassals of Francia. They stopped being Norsemen and became Normans. Yet they were hardly less warlike than their forebears, and maintained better connections with Scandinavia than with England. Relations between Aethelred and the previous count, Richard I, called Sans-Peur, “the Fearless,” had soured to the point that in AD 991 Pope John XV intervened, sending a legate to bring them to an agreement. By the Peace of Rouen, both agreed not to aid each other’s enemies. In 996, however, both Richard and John died, and as Richard II – the first Norman to be styled as Duke – was still in his minority, his Danish mother and Norman uncle ruled as regents. For them to allow Forkbeard and his Vikings to cross the South Sea, shelter safely in their harbors, and sell their ill-gotten English booty was a violation of the peace. Now it was 1001, the dawn of the new millennium. To the poor beleaguered English it seemed nothing had changed. As the Chronicle recorded, “In England this year there were constant raids by the pirate army, who harried and burnt almost everywhere.” The Danes came raiding into Hampshire, practically to the doorstep of the Old Minster at Winchester. They sailed up the River Exe and laid siege to Escanceaster (“Fortress on the Exe,” modern Exeter), but the town was more than the typical Anglo-Saxon burh, a village defended by earthworks and stockade. Like London, it had been founded and fortified by the Romans as a military post, with stone walls the Vikings were unable to overcome. They vented their frustration on the surrounding villages and defeated the armies of Devon and Somerset in the field. But if Aethelred could not stop Vikings from preying on England, he could at least see to it they found neither shelter nor markets in Normandy. Our story begins the way it will end: with invaders from the sea.

REVIEWS:

Mr. Hollway meticulously ties all of the elements together into a cohesive story and timeline…. Exhaustively researched and sourced, and exceptionally written, Mr. Hollway has assembled another masterclass in how to tell a multi-faceted story of history in one fell swoop. For those looking to get a grasp on early English history and the beginnings of the British monarchy, “Battle for the Island Kingdom” is a perfect selection. For those simply looking for a fun, yet bloody read, you can’t go wrong with Mr. Hollway’s latest.

This new book by Don Hollway ambitiously sets out to describe the complex interplay between competing European royal houses during what academics call ‘The Second Viking Age’.... Men and women feature in equal measure in the book, and family inter-relationships become important threads throughout the narrative. The author brings to life the Court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm.

The author brings to life the court intrigues and bitter rivalries dividing Europe’s nobility, shedding light on an otherwise dark period of our history, when judicial murder and a resort to arms was the norm. The narrative builds on the evidence of Scandinavian sagas, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and the works of Norman historians.... Battle for the Island Kingdom is thoroughly enjoyable, and is recommended to anyone looking for a comprehensive and accessible history of the period.

In his latest work on this era, the author brings this period to vivid life through engaging prose, a coherent narrative and a mind for the most minute yet interesting detail. The references from relevant source material are plentiful but do not bog down the storytelling. This book is lively and easy to read. Most readers know about the Battle of Hastings and its outcome and while this book informs on that event, fewer know about the events leading up to it, but this work delivers that to the reader as well.

Hollway’s book is anything but dry. At every turn, he infuses his accounts with a novelist’s flair.... Hollway makes it feel so loud and headlong that the story feels both new and unpredictable. Just as with The Last Viking,� he’s filled a long-lost era with color and life.

Historian Hollway chronicles in this brisk study the 66 tumultuous years culminating in the Norman victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 CE…. Despite the outcome being well-known, Hollway’s suspenseful buildup during William’s rise as a credible threat to Harold pays off in his recounting of the epic battle. Throughout, Hollway explains frankly when source material may be questionable, and his footnotes clarify the path leading to the Norman Conquest. The result is an accessible and vibrant portrait of a turning point in world history.

There’s no need for fictional dragons when the real-life battle for thrones and empires is as thrilling as Hollway’s.... A deeply researched must-read for anyone interested in this contested era. Readers will be enthralled with quotations from period accounts and insights into the harsh reality of the violent, often short lives of Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman nobility. ORDER TODAY:

• AMAZON • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Author/historian/illustrator Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His first book, The Last Viking, a gripping history of King Harald Hardrada, was acclaimed by The Times of London and Michael Dirda, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Washington Post. Hollway is also a classical rapier fencer and historical re-enactor. His work is also available across the internet, a number of his pages scoring extremely high in global search rankings.

More from Don Hollway:

|

oday the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity in Winchester, England is one of the largest cathedrals in Europe.

oday the Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity in Winchester, England is one of the largest cathedrals in Europe.